Living with CRPS: the end of the “worst pain” myth.

You've probably heard Complex Regional Pain Syndrome called "the most painful condition in the world." in social medias. Unfortunately, that claim is not only wrong, it's actively harming patients. Here's what the science actually tells us, and why understanding the reality of CRPS offers more hope than the myth ever could.

Introduction: When myths become medicine

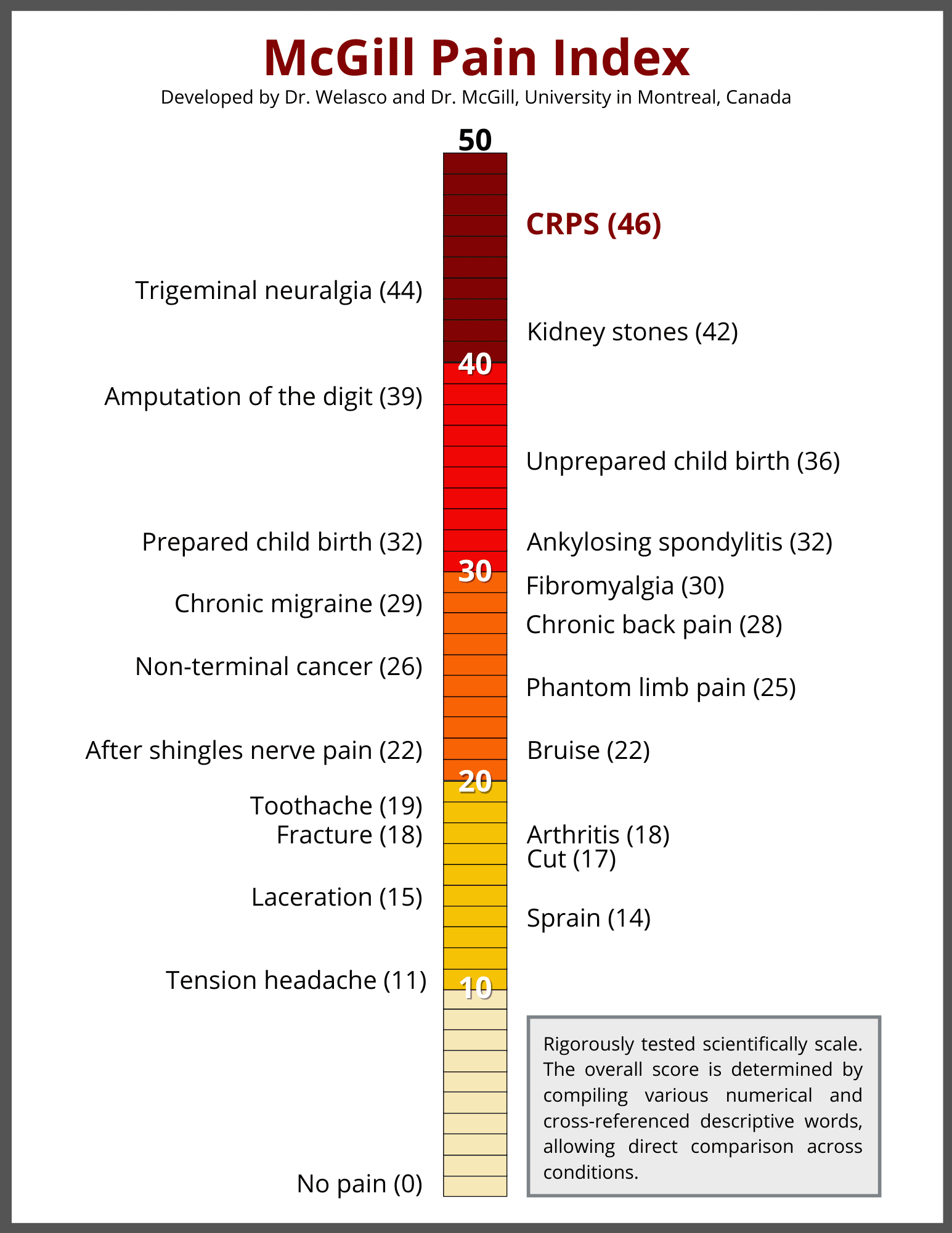

Search “CRPS” online and within seconds you’ll find the claim: “the most painful condition known to medicine, ranking higher than amputation, childbirth, and cancer on the McGill Pain Scale.” It sounds quite authoritative. It’s been repeated thousands of times on social media, patient forums, and advocacy websites. And it’s completely false.

This isn’t just about research accuracy, it’s about a tool being used for something it was never designed to do.

When patients receive a CRPS diagnosis and immediately encounter this catastrophic narrative, something profound happens in their nervous system. The belief that pain is uncontrollable and will only worsen (what researchers call catastrophizing) becomes one of the strongest predictors of poor outcomes in CRPS (Lohnberg & Altmaier, 2013). In other words, the myth itself may be making people worse.

What the McGill Pain Scale actually is (and isn’t)

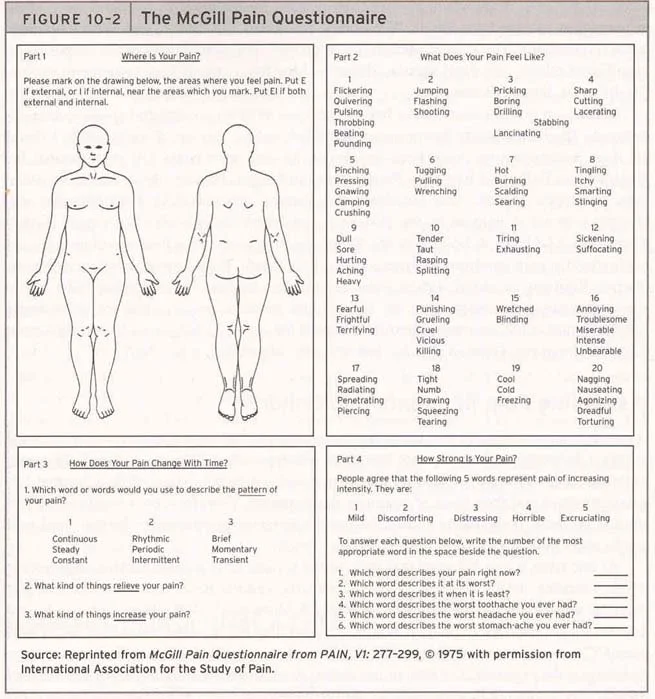

This is the McGill Pain Questionnaire

The McGill Pain Questionnaire, developed by Melzack and Torgerson in 1971, was never designed to rank different conditions against each other. It’s a tool that measures how individual patients describe their own pain experience using descriptive words like burning, shooting, stabbing, or aching. The questionnaire contains 78 pain descriptors organized into 20 groups, and patients select the words that best match what they’re feeling. This creates a profile of their pain experience and gives healthcare providers a more detailed picture than just asking “how much does it hurt on a scale of 1 to 10.”

Importantly, the McGill Pain Questionnaire was designed to track how one person’s pain changes over time or to understand the quality of their pain, not to compare who has it worse between different diseases. You can’t use it to say “CRPS hurts more than cancer” any more than you could use a thermometer to say “fevers are worse than frostbite.” They’re measuring different experiences in different people at different times.

The “CRPS is worst” claim emerged from a mix of small sample observations, well-meaning advocacy trying to draw attention to an under-recognized condition, and endless internet repetition, not from systematic scientific comparison.

Why social media loves pain competitions

There’s a reason this myth spreads so easily on social media. Platforms thrive on engagement, and nothing drives clicks and shares like superlatives and competition. “The worst pain ever” is more clickable than “a complex neuroimmune condition with variable outcomes.” Pain hierarchies create drama, they generate comments and debates, they make people feel seen if they have the “winning” condition or defensive if they don’t.

This isn’t unique to CRPS. You’ll find similar claims about trigeminal neuralgia, cluster headaches, kidney stones, and others, all supposedly ranking highest on scales that were never meant to create these rankings. Social media algorithms reward extreme claims with visibility, advocacy groups sometimes amplify them hoping to attract research funding and attention, and patients caught in the middle end up with a narrative that prioritizes drama over actual understanding or treatment.

The problem is that this competition serves social media platforms and engagement metrics, not patients. It creates a culture where suffering has to be “the worst” to be taken seriously, where validation comes from pain comparisons rather than from being heard and helped.

What we’ve been missing while chasing myths

Here’s what really bothers me about all this: while we’ve been busy sharing dramatic claims about pain rankings, researchers like Johnston and colleagues pointed out in 2015 that we have almost no research on what it’s actually like to live with CRPS. “Literature on the lived experience of Complex Regional Pain Syndrome is non-existent,” they wrote. So, while we are arguing about pain scores we are completely missing the bigger picture of what patients are actually going through. And to me, this is what matters the most. Pain is never a competition.

The real story of CRPS is more nuanced and more hopeful: it’s a treatable neuroimmune condition with a critical intervention window. Miss that window, and yes, you’re dealing with changes that are much harder to reverse. Catch it early, and 60 to 80% of patients significantly improve.

This article brings together recent research on CRPS mechanisms, the first comprehensive qualitative studies of patient experience, and emerging evidence about why the first three months matter more than we ever realized.

1. Three systems gone wrong: here is the neuroscience of CRPS

Think of your nervous system as a smoke alarm (yes, I know, everyone uses this analogy). Normally, it alerts you to real danger: a burn, a break, a threat. In CRPS, that alarm gets stuck in the “on” position, blaring long after the initial injury has healed. But recent research shows it’s not just a faulty alarm. CRPS involves three different biological systems going wrong at the same time, and understanding this completely changes how we think about treatment timing.

a) The autoimmune attack.

Andreas Goebel’s research group in Liverpool found specific autoantibodies in CRPS patients: IgG antibodies that attack receptors in the autonomic nervous system (Kohr et al., 2011; Dubuis et al., 2014). This isn’t “all in your head.” It’s your immune system mistakenly attacking your own nervous tissue. Some patients have responded to immunotherapy, which opens up entirely new ways to treat this. This discovery reframes CRPS from a mysterious pain syndrome to an autoimmune disorder with actual biological markers we can identify.

b) The neuroinflammation cascade.

Your brain’s immune cells (called microglia) become activated and stay activated, keeping inflammation going in both the affected limb and the central nervous system (van Rijn et al., 2011). This explains the thing that terrifies patients most: spread. CRPS can extend beyond where you were originally injured, but it’s not the injury itself “spreading.” It’s your central nervous system becoming globally hypersensitive, a progression of how your whole system processes signals rather than the condition physically moving to new areas.

c) The brain remapping itself.

Perhaps most interesting are the fMRI studies by Maihöfner and colleagues (2003-2007) showing that within weeks of CRPS starting, the brain literally reorganizes itself. The area of your brain that represents your affected hand shrinks, your body image becomes distorted, pain pathways become hypersensitized. When Johnston-Devin and colleagues interviewed CRPS patients in 2021, they described their affected limb as feeling “huge and foreign, like it doesn’t belong to my body anymore.” They weren’t imagining it. Brain imaging confirmed what they were experiencing: measurable changes in how the brain is organized that validate what they were going through.

What makes this three-system understanding critical is timing. Each system has a window when it’s still changeable. The autoimmune cascade is most active early on. Neuroinflammation can be interrupted before it becomes self-sustaining. The brain reorganization is reversible, but becomes increasingly fixed over months. This is why the first 12 weeks matter so much.

Recent advances in wearable technology using continuous skin temperature monitoring and movement sensors are now providing objective data that bridges the gap between these biological mechanisms and what patients actually experience day to day. We finally have tools that validate what patients have been telling us all along.

2. Living with CRPS: the end of the “worst pain” myth.

For years, researchers focused on understanding how CRPS works in the body. But nobody was really documenting what patients were going through day to day. In 2021, Johnston-Devin and colleagues interviewed 17 people with CRPS to understand their actual experiences. Some had been dealing with symptoms for just 4 months, others for 18 years. What they found shows why understanding the biology is only part of the picture.

1) Getting diagnosed can take years, and that delay causes real harm.

In this study, the time between first symptoms and getting an actual CRPS diagnosis ranged from 3 weeks to 9 years. On average, it took 2.65 years. During that time, patients described being called “a hypochondriac, hysterical teenager” or being told “it’s all in your head.” They went from specialist to specialist, got wrong diagnoses, tried treatments that didn’t work, and drained their savings. One person described it as a “quest,” which might sound almost adventurous until you realize it meant years of not being believed while your nervous system was fundamentally changing.

Even after diagnosis, many found themselves in a healthcare system that didn’t really understand CRPS. The condition still goes by outdated names in many places (Reflex Sympathetic Dystrophy, algodystrophy). Patients talked about physiotherapists who made their pain worse with inappropriate treatment, doctors who admitted “I didn’t really know what to do with you,” and emergency rooms that assumed “of course you’re going to be in pain” and dismissed new symptoms.

2) The fear that it will spread takes over your life.

Even when patients get their symptoms under control, they live with constant worry. Will a small injury cause it to spread? Will surgery trigger a flare? CRPS can come back or spread after an injury, surgery, illness, stress, tiredness, or sometimes for no clear reason at all. One patient described it this way: “You just get a pain somewhere out of nowhere and you’re just like ‘no, it’s not spreading, leave me alone, go away’.”

This isn’t catastrophizing or being dramatic. It’s a completely rational response to a condition that genuinely can progress in unpredictable ways.

3) The practical impact reshapes your entire life.

Of the 17 patients Johnston-Devin interviewed, 11 had to stop working completely and two had changed jobs. One said: “It’s ruined me. I’ve used all of my savings that I had, and just sort of try and make it fortnight to fortnight.”

But the losses go beyond money. Patients described the exhausting work of pacing yourself (knowing you should stop before the pain starts, but finding it nearly impossible on a good day). They talked about feeling guilty for not being able to help around the house anymore, about friends who gradually drift away, and about struggling with who they are when their body no longer does what it used to.

Perhaps the most damaging part was not being believed by healthcare providers. Patients described being told in hospital: “Oh you look fine, you’ve got a smile on your face. You know you wouldn’t be smiling if you were really in that much pain.” Others found that even when doctors believed they had CRPS, it didn’t necessarily improve their care. Assumptions about the condition sometimes led to new or worsening symptoms being dismissed.

What Johnston-Devin’s research really shows is that CRPS isn’t just a medical problem that needs medical treatment. It’s an experience of trying to navigate a healthcare system that isn’t prepared for complex pain, having to advocate for yourself when you’re at your most vulnerable, and rebuilding your sense of self when your body has fundamentally changed.

One patient put it perfectly: "Because the hardest thing is that my life is not my own. You make the decisions as to what my life is going to be, and I've got to do whatever I can to convince you to help me because I'm stuffed without you."

3. The first three months are critical

Here’s what long-term studies tell us: the first 12 weeks after CRPS starts are make or break. During this window, your nervous system is still flexible, still changeable. The inflammation is active but not yet locked in. The brain changes are happening but can still be reversed. After 3 to 6 months, those brain changes become more permanent, and the condition shifts from being mainly a problem in your limb to a central nervous system disorder.

—> What early intervention actually looks like.

Moseley’s research (2004, 2008) on graded motor imagery showed we can directly target those brain changes. Mirror therapy essentially “tricks” the brain back into seeing the body normally. Physical therapy that focuses on what you can do (not on reducing pain) combined with psychological support to prevent catastrophic thinking can interrupt the cycle before it becomes self-sustaining. The goal isn’t to make your hand completely pain-free. It’s to get your hand working again.

But here’s the problem: the old advice to rest and protect the affected limb actually makes CRPS worse. It reinforces the brain’s belief that the limb is damaged and needs protection. Movement is medicine, even when it’s uncomfortable. Yet patients in Johnston-Devin’s study described physiotherapists who were “very unsupportive, almost as though he really didn’t believe the level of pain that I was in,” and treatments that caused more harm than help.

—> What patients actually need during this window.

Johnston-Devin and colleagues identified some critical things that healthcare providers often miss:

Patients need to know their pain is real without making it sound like the end of the world. Yes, this is real and it hurts, but that doesn’t have to mean this is the worst thing that could happen.

They need to understand what’s actually happening. People do better when they understand they’re dealing with nervous system reorganization, not just inflammation in their limb.

They need care focused on function rather than pain scores, and they need some sense of control and agency. Feeling completely helpless becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The difference between catching CRPS in this early window versus treating it after it’s been established for months or years is huge. Think of it like a fresh wound versus an old scar. A fresh wound responds really well to proper care. An old scar? You can improve it, but you’re working against established tissue changes.

—> The approach that shows promise.

Johnston-Devin’s research found that patients who went to multidisciplinary pain clinics with knowledgeable professionals reported better healthcare, better health outcomes, and more resilience than those who didn’t. The approach isn’t complicated: early diagnosis, intensive treatment from multiple specialists, validation of what the patient is experiencing, and treating the patient as a partner in their care. But it requires a healthcare system that recognizes how critical those first three months are and actually acts on it.

4. Moving from warriors to partners

Johnston-Devin and colleagues found that patients described themselves in two different ways: sometimes as “warriors” and sometimes as “prisoners of war.” The warrior identity showed up when people felt resilient, when they were problem-solving and finding ways forward despite enormous challenges. The prisoner identity showed up when they felt they had no options, no control, when they were at the mercy of CRPS rather than living their lives. The difference between these two states often came down to one thing: being heard.

What changes outcomes isn't just biology. Patients who found knowledgeable healthcare providers, who were believed and validated, who understood what was happening in their nervous system, who had their ability to function prioritized over their pain scores, these patients developed resilience. They described “unleashing the warrior within” after working with pain psychologists. They found support from other patients online (though they also encountered plenty of catastrophic stories). They advocated for themselves and raised awareness through initiatives like “Color the World Orange Day.”

But patients who went years without a diagnosis, who met dismissive or unknowledgeable providers, who were told to rest when they should have been moving, who felt they had to “convince” doctors to help them, these patients remained prisoners. The biology matters, but so

The myth costs more than we realized. Johnston and colleagues wrote back in 2015 that “patient experiences should inform National Pain Strategies,” but we’re still leading with “worst pain in the world.” We’re activating fear and catastrophizing right at the moment of diagnosis. We’re setting up a fight between patient and body rather than a partnership to retrain the nervous system.

What if we said this instead: “You have CRPS, a condition where your nervous system has become hypersensitive. The next three months are really important. We’re going to work together to retrain your brain, calm down the inflammatory response, and keep you functioning. This will be uncomfortable, but we have approaches that work if we use them now.”

Johnston-Devin's proposed model of CRPS lived experience highlights issues healthcare providers rarely recognize: the exhausting work of activity pacing, the guilt of changed family roles, the financial devastation, the fear of spread, the vulnerability of depending on providers who may not believe you. Using this model in clinical care could transform patient-provider interactions from patients having to "convince" providers to help them, to genuine partnerships where both parties bring essential expertise.

Conclusion: The real conversation we should be having to help people with CRPS

How many people are living with chronic, entrenched CRPS simply because nobody told them about the three-month window? How many were told to rest during the exact period when their nervous system was most changeable? How many believed the “worst pain in the world” myth and catastrophized their own outcomes?

We know what’s happening now. We understand the autoimmune attack, the neuroinflammation, the brain reorganization. We have treatments that work. We have patient voices finally telling us what they need. We have a window of opportunity measured in weeks, not years.

But we’re still sharing myths instead of mechanisms. We’re still measuring pain intensity instead of listening to lived experience. We’re still missing the window.

Johnston-Devin and colleagues found that the difference between patients who become warriors versus prisoners often comes down to whether they were heard, believed, and treated as partners during those critical first months.

The question isn’t whether CRPS is the “worst pain in the world.” That’s the wrong question, based on a misunderstood tool, feeding a harmful myth. The real questions are: Are we catching it early enough? Are we treating it aggressively enough? Are we listening carefully enough?

Every person diagnosed with CRPS today will Google their condition tonight. They’ll find the myth. And tomorrow, during that critical window when treatment works best, they’ll either find a healthcare provider who understands the biology and respects the lived experience, or they won’t.

That’s the conversation we should be having.

If you are interested to read more, I would be happy to send you this article published in 2021 in The Journal of Pain by Johnston-Devin,et al. “Patients describe their lived experiences of battling to live with complex regional pain syndrome".

References:

Dubuis, E., et al. (2014). Longstanding complex regional pain syndrome is associated with activating autoantibodies against alpha-1a adrenoceptors. Pain, 155(11), 2408-2417.

Grieve, S., et al. (2017). Recommendations for a first core outcome measurement set for complex regional pain syndrome clinical studies (COMPACT). Pain, 158, 1083-1090.

Grieve, S., et al. (2019). A multi-centre study to explore the feasibility and acceptability of collecting data for complex regional pain syndrome clinical studies using a core measurement set: Study protocol. Musculoskeletal Care, 17, 249-256.

Johnston, C. M., Oprescu, F. I., & Gray, M. (2015). Building the evidence for CRPS research from a lived experience perspective. Scandinavian Journal of Pain, 9(1), 23-27.

Johnston-Devin, C., Oprescu, F., Gray, M., & Wallis, M. (2021). Patients describe their lived experiences of battling to live with complex regional pain syndrome. The Journal of Pain, 22(9), 1111-1128.

Kohr, D., et al. (2011). Autoimmunity in complex regional pain syndrome. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1261(1), 74-80.

Lohnberg, J. A., & Altmaier, E. M. (2013). A review of psychosocial factors in complex regional pain syndrome. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 20(2), 247-254.

Maihöfner, C., et al. (2003). Cortical reorganization during recovery from complex regional pain syndrome. Neurology, 63(4), 693-701.

Matamala-Gomez, M., et al. (2021). Virtual reality for pain management in complex regional pain syndrome: A systematic review. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 10(6), 1292.

Melzack, R., & Torgerson, W. S. (1971). On the language of pain. Anesthesiology, 34(1), 50-59.

Moseley, G. L. (2004). Graded motor imagery is effective for long-standing complex regional pain syndrome. Pain, 108(1-2), 192-198.

Moseley, G. L. (2008). Graded motor imagery for pathologic pain. Neurology, 67(12), 2129-2134.

Parkitny, L., & Stanton, T. R. (2023). Genetic factors in complex regional pain syndrome: Current evidence and future directions. European Journal of Pain, 27(4), 412-428.

van Rijn, M. A., et al. (2011). Spreading of complex regional pain syndrome: not a random process. Journal of Neural Transmission, 118(9), 1301-1309.

Dr. Caroline Racz is a family physician working in chronic pain medicine and Assistant Professor at Dalhousie University, specializing in complex pain conditions and patient education.